Washington State - 538 Wine Notes

Washington’s first wine grapes were planted at Fort Vancouver by the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1825. By 1910, wine grapes were growing in many areas of the state, following the path of early settlers. French, German and Italian immigrants pioneered the earliest plantings. Wine historians Ron Irvine and Dr. Walter Clore document in their book The Wine Project a continuous and connected e ort to cultivate wine grapes beginning with those early plantings at Fort Vancouver. Hybrid varieties arrived in nurseries in the Puget Sound region as early as 1854, and by 1860 wine grapes were planted in the Walla Walla Valley.

Large-scale irrigation, fueled by runoff from the melting snowcaps of the Cascade Mountains, began in eastern Washington in 1903, unlocking the dormant potential of the land and its sunny, arid climate. Italian and German varietals were planted in the Yakima and Columbia Valleys and wine grape acreage expanded rapidly in the early part of the 20th century. In 1910, the first annual Columbia River Valley Grape Carnival was held in Kennewick. By 1914, important vineyards had sprung up in the Yakima Valley—most notably the vineyards of W.B. Bridgman of Sunnyside. Muscat of Alexandria vines on Snipes Mountain dating to 1917 are still producing and are considered the oldest in the state.

The arrival of Prohibition in 1920 put a damper on wine grape production, but ironically may have helped spawn early interest in home winemaking. At the end of Prohibition, the first bonded winery in the Northwest was founded on Puget Sound’s Stretch Island. By 1938 there were 42 wineries located throughout the state.

The first commercial-scale plantings began in the 1960s. The efforts of the earliest producers, predecessors to today’s Columbia Winery and Chateau Ste. Michelle, attracted the attention of wine historian Leon Adams. Adams in turn introduced pioneering enologist Andre Tchelistcheff to Chateau Ste. Michelle. It was Tchelistcheff who helped guide Chateau Ste. Michelle’s early e orts and mentored modern winemaking in this state. The resulting rapid expansion of the industry in the mid ‘70s is now rivaled by today’s breakneck pace, where a new winery opens nearly every 15 days.

The trend for quality wine production started by a few home winemakers and visionary farmers has become a respected and influential $4.4 billion-plus industry within Washington State. Washington wine is available in 50 states and more than 40 countries globally. Washington ranks second nationally for premium wine production and over 50,000 acres are planted to vinifera grapes. Over 40% of these vines have been planted in the last 10 years as the industry rapidly expands. The vast majority of wineries in Washington are small, family producers making less than 5,000 cases annually. In fact, of the state’s 900+ wineries, only about 20 make more than 40,000 cases annually. The small, artisan nature of the industry contributes to producing wines of exceptional quality.

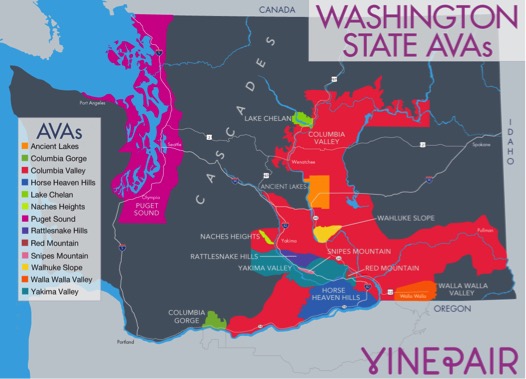

The Cascade Mountains are the most important landmark in Washington State. Though the area around Puget Sound does produce some wine, the more important wineries are east of the Cascades. The mountain range provides the shift from the cold and rainy Northwest to the arid, warmer slopes around the Columbia Valley. Long, warm days and cool nights in the growing regions create a large diurnal shift, which helps maintain the natural acidity of the grapes. Washington State has some of the most dramatic fluctuations of any wine region in the world with up to 40 degree difference between daytime high and nighttime low temperatures. The higher levels of natural acidity contribute to making the wines more food friendly and also assist with their longevity. In the traditional grape-growing model, wineries are located next to or close to their vineyard sources. Washington, generally, completely breaks this model. Many wineries are located dozens and even hundreds of miles from the vineyards they work with. Additionally, many contract their grapes rather than establishing their own vineyards.

This gives the wineries several advantages. First, purchasing grapes minimizes the startup time for a winery and has enabled the industry’s rapid growth. Second, it allows wineries to set up shop wherever they like, be it near the consumer hub of Seattle or in the far reaches of the state that they call home. Third, not being tied to a single vineyard source in a single location means that wineries can experiment with vineyards across Washington. They can make a wine that blends, say, Cabernet Sauvignon from the Horse Heaven Hills with Merlot from Red Mountain and Petit Verdot from the Wahluke Slope, taking what they feel is the best from each location. Using a diversity of sites also helps keep quality consistent across vintages. Lastly, working with a diversity of sites in different locations also helps protect against disruptions caused by Washington’s occasional spring and fall frosts and winter freezes.

· Washington is the second largest wine-producing region in the U.S.

· As of 2016, there are 900+ wineries in the state, with the number more than doubling in the last ten years.

· Washington is not defined by a single grape variety, with over 40 varieties planted.

· Varietal typicity, pure fruit flavors, and a blend of Old World and New World styles are the hallmarks of Washington’s wines.

· Washington wines consistently offer high quality and value across a range of price points.

Which grapes grow well? The question may be, “Which grapes don’t grow well?” It is quite clear to all that Washington State faces a double-edged sword in this respect: this region makes at least 3 to 4 varietal wines on a truly world-class level (when many places would be excited about one), which is amazing. However, when one says Washington State, what grape do you picture? Napa has Cabernet sauvignon. Oregon has Pinot noir. New Zealand has Sauvignon blanc. Which one is Washington State’s rock star? Riesling? Merlot? Cabernet Sauvignon? Syrah? Not to mention Semillon, Viognier, Grenache and (it looks like) Tempranillo? What may be a marketing challenge to some is a boon on the quality front. Merlot may have been a first big splash, but there is no denying that they have made headway with other grapes on an international scene, as well. Maybe one will emerge in the world’s eye, but we aren’t worried about that. Washington is blessed with one of the greatest climates for a whole lot of grapes in the world. Even if they must make 120 world class wine types.

Washington has 13 federally approved growing regions that offer a diversity of climates, soil types, and growing conditions that allow a wide variety of grapes to grow well. These range from warm sites such as Red Mountain to cool regions like the Puget Sound and areas in between.

The relationship to the Missoula Floods, a series of cataclysmic events, defines the soil types of the vineyards in Washington. Most vineyards lie below the floodwaters with soils of loess—wind-blown deposits of sand and silt— overlying gravel and slack water sediment with basalt forming the bedrock. This provides a diversity of soil types that are well drained and ideal for viticulture.

The top four grape varieties all vie for the top spot, depending on the vintage. In 2015, Cabernet Sauvignon made up 21% of tonnage, followed by Riesling at 19.8%, Chardonnay at 18.9% and Merlot at 15.8%.

Washington also make sparkling, fortified and late harvest dessert wines (some of which, in colder years, are true ice wines). Grapes that many people think will do exceptionally well in the future are the warm to hot climate varieties like Tempranillo, Grenache, Sangiovese, Mourvédre and Cinsault. For the cooler areas of our state, we can make outstanding Cabernet Franc, Malbec, Petit Verdot and Nebbiolo (yes, that Nebbiolo). On the Western side of the Cascade Mountains, they make new efforts with such esoteric crosses as Madeline Angevine and Scheurrebe – not to mention the latest hot ticket, Pinot noir.